Dr. Seuss is one of the most popular American children’s authors around the world. His writing, stories, and illustrations have influenced American culture, homes, and classrooms. But is Dr. Seuss influencing young children in a way that is reflecting them and others around them in a positive and kind way?

Suess had a career as a political cartoonist during WW2, for the New York newspaper PM. Suess often incorporated explicit anti-Semitism, anti-Asian, and anti-Mexican illustrations. Dr. Seuss’ “1933 political cartoon in Vanity Fair depicted ‘Mexico’ as a knife-wielding Mexican man in an oversized sombrero lighting a bomb and an Asian man holding a ‘Yellow Peril’ flag” (Ishizuka, pg. 4). Another example is the cartoon below, illustrating Japanese people in California, lining up to collect explosives, depicting them as a violent threat to the United States.

(Bourne)

Suess later went on to publish many children’s books, that became very popular around the world. Some of his best-known books are Horton Hears a Who, The Lorax, and The Cat In The Hat. The National Education Association signed a 20-year contract with Dr. Suess to promote early literacy through RAA (Read Across America), from 1997 to 2017. RAA is specifically celebrated during Suess’s birthday, which is March 2nd. Suess’s contract with RAA has recently ended, and RAA began to distance itself from Seuss in 2018. RAA acknowledges the need for diverse books, and the “brand is now one that is independent of any one particular book, publisher, or character” (Association).

There are many examples of Dr. Seuss’ books and illustrations dehumanization of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color). Portraying Black people as gorillas or monkeys shown holding spears, wearing grass skirts, or having flys swarming around them, and using the N-word in his captions. Representing the people of Asia as a monolith, instead of understanding the different cultures, languages, clothing, food, beliefs, etc. In his book, And I Think I Saw it on Mulberry Street, Asian people were described as ‘chinaman’, with lines for eyes, wearing a pointed hat, carrying chopsticks and a bowl of rice. He drew Indigenous people wearing feathers, smoking pipes, and being nearly naked.

Additionally, sexist stereotypes are presented in his children’s books. White women and girls retain minimal speaking roles or are rarely present. If present they are often cooking, serving, or taking care of children. Women and children of color are completely absent across his many children’s books.

“When children’s books center Whiteness, erase people of color and other oppressed groups, or present people of color in stereotypical, dehumanizing, or subordinate ways, they both ingrain and reinforce internalized racism and White supremacy”

(Ishizuka, pg. 7).

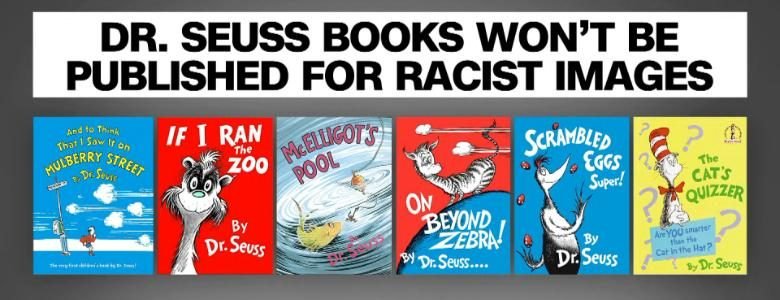

In 2021, Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced that they will stop printing six Dr. Seuss books due to racist and sensitive imagery. The following books will no longer be published: McElligot’s pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, The Cats Quizzer, If I Ran A Zoo, and And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street (Gross).

It is important to stay aware of the content in the books listed above, Suess’ other works of writing and his political cartoons. Consider the messaging these images give to children for whom these books are windows, impacting how they view others, and mirrors, impacting how the child views themself.

Works Cited

Aspegren, Elinor. “‘Read across America Day,’ Once Synonymous with Dr. Seuss, Is Diversifying. Here’s Why Things Have Changed.” USA TODAY, 1 Mar. 2020, www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2021/03/01/read-across-america-day-dr-seuss-diversity-racism/6878454002/. Accessed 6 Mar. 2021.

Association, National Education. “Read across America: Frequently Asked Questions | NEA.” Www.nea.org, 28 Jan. 2021, www.nea.org/resource-library/read-across-america-frequently-asked-questions. Accessed 6 Mar. 2021.

Bourne, Alden. “Redirect Notice.” Google.com, 20 Sept. 2017, www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.wnpr.org%2Fpost%2Fseuss-museum-premature-discuss-plans-address-racist-cartoons&psig=AOvVaw35DdkaWBzXfhCgj9H73xQA&ust=1615079955870000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CA0QjhxqFwoTCLCpquq_mu8CFQAAAAAdAAAAABAc. Accessed 6 Mar. 2021.

Gilbert, Sophie. “The Complicated Relevance of Dr. Seuss’s Political Cartoons.” The Atlantic, The Atlantic, 31 Jan. 2017, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/01/dr-seuss-protest-icon/515031/.

Gross, Jenny. “6 Dr. Seuss Books Will No Longer Be Published over Offensive Images.” The New York Times, 2 Mar. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/03/02/books/dr-seuss-mulberry-street.html#:~:text=Mr.%20Geisel%2C%20whose%20whimsical%20stories. Accessed 3 Mar. 2021.

Ishizuka, Kazuo. “Quantitative Analysis of Electron Microcopy Data.” Materia Japan, vol. 58, no. 2, 1 Feb. 2019, pp. 68–72, sophia.stkate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1050&context=rdyl, 10.2320/materia.58.68.

CNN. “Dr. Seuss’ 6 Books Won’t Be Published Anymore,” CNN, 3 Mar. 2021. Accessed 5 Mar. 2021.